Co-developing Language Linkages and Digital Infrastructure Components

During early engagements and workshops, the Arctic Genomics team met with partners across Nunavut and

Nunavik, focusing on the community of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. The Ekaluktutiak Hunters & Trappers

Organization in Cambridge Bay has carried out a long-term community-based monitoring project with

scientists at the University of Calgary, so these partners had much to share about the utility of

wildlife genomics science in monitoring the health of wildlife that are keystones of cultural

connection and community health. A long-term relationship also existed between the Kitikmeot

Heritage Society (KHS) and Carleton University in support of KHS digital strategies and priorities

to communicate and maintain culture.

From these trusted relationships, the Arctic Genomics

and Canada Biogenome Knowledge Mobilization teams discussed other priorities of the communities, and

language preservation and development surfaced as a key priority to support cultural preservation,

and also as a pathway to make genomics science more broadly understandable and implementable for

other Inuit communities (and beyond) with their community-based environmental monitoring strategies.

Throughout this project, we have been working with Inuit partners to make useful linkages between

new and existing Inuinnaqtun terms and the genomics world.

Concepts and terms between the

genomics world and those in Inuit ways of knowing and being often do not have one-to-one

translations; this work acknowledges that Inuit knowledge and protocols and distinct and separate.

Translated linkages between the two worlds do, however, serve to break down barriers to the use of

genomics for Inuit communities. The translations support communities in making informed decisions,

combined with the information in our knowledge mobilization system — the information is made more

accessible to those outside of these collaborative efforts and programs.

Complex terms translation is supported by the world of semantics - understanding language itself as symbolic representation and metaphor. Working with Inuit partners to meet the Inuinnaqtun language preservation priorities of KHS and the Elders-In-Residence, the broader team participates in the CEBP by translating science knowledge concepts as bridges of understanding to each other's way of knowing and being.

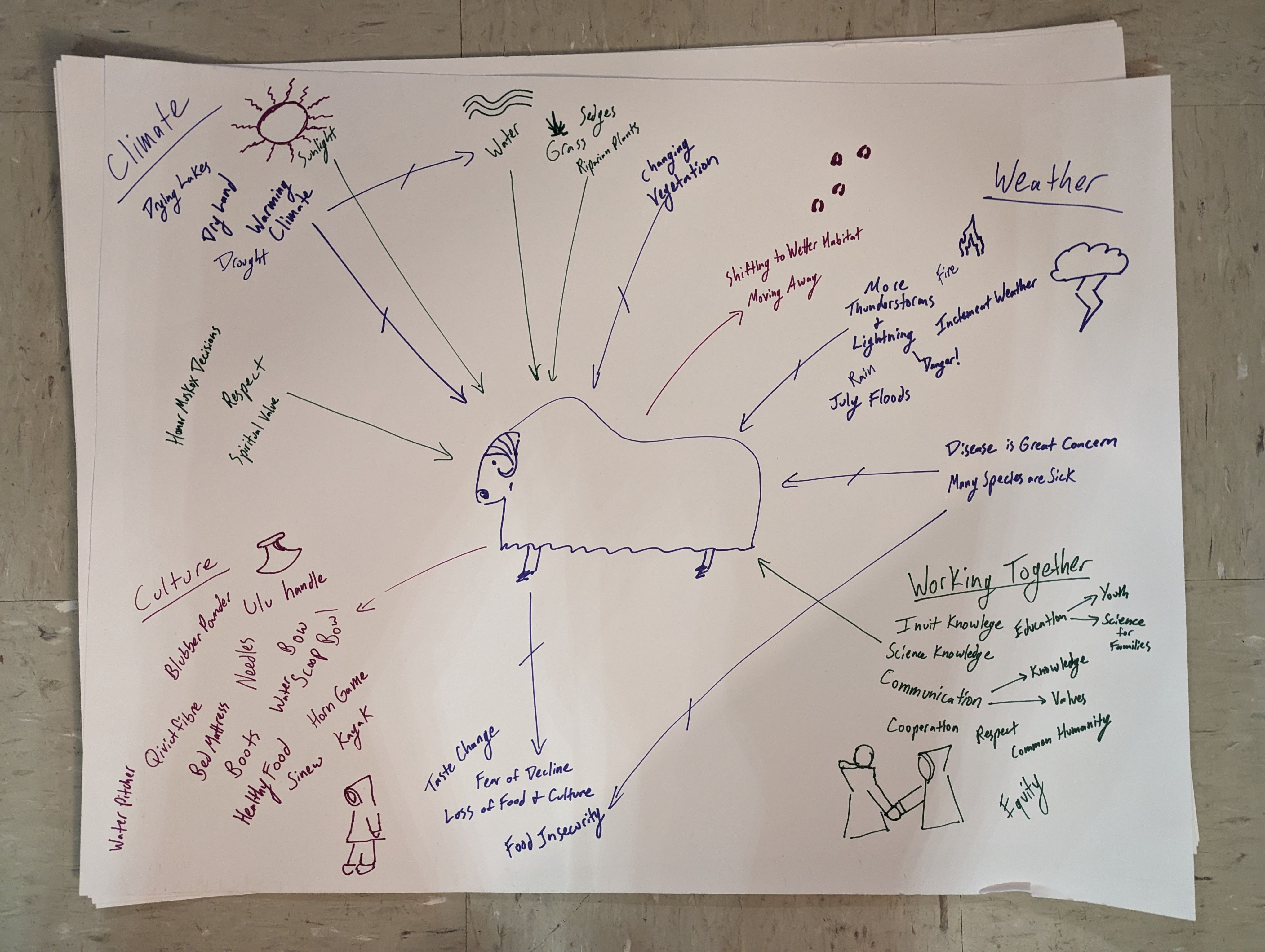

Pictured Here: An image of a symbolic representation of Inuit social and natural ecology as it centers around Muskoxen, a keystone cultural species for the community of Cambridge Bay. This image was co-created during a workshop in Cambridge Bay, NU at the Canadian High Arctic Research Centre (CHARS) wherein KHS Elders-In-Residence (Mabel Etegik, Emily Angulalik, and Bessie Omilgoetok) described the aspects depicted as they were translated in real-time by Emily Angulalik and transcribed by McCaide Wooten and Srijak Bhatnagar. Such knowledge maps are transcribed into digital concept mapping tools; the concepts and relationships are then encoded into the knowledge model; the knowledge model is then represented in (and associated resources made available through) the knowledge graph database. Photo credit: Christy Caudill

Pictured here: McCaide Wooten presents the findings from listening sessions with the Elders to workshop participants from Cambridge Bay and across Nunavut, Nunavik, and Canada.

In developing the knowledge mobilization system, we look to our partners to detail the protocol

around their shared knowledge and its use, including the newly developed Inuinnaqtun terms. KHS and

Carleton University have partnered with Local Contexts, an Indigenous-led organization that has

created a mechanism for Indigenous communities to customize and persist metadata tags to exercise

authority and sovereign rights over their intellectual property, cultural and other heritage,

genetic resources, and knowledge. Data in our system that carries these tags include terminology,

Indigenous Knowledge, and verification of proper engagement in co-development. KHS are creating

other metadata labels for data in the system will assert Inuit as traditional guardians of Arctic

species, and as such, collaboration should occur with any research in Inuit Nunangat and with

species of cultural importance.

This system has been developed in adherence to Indigenous data governance protocols and research

strategies. The vision is unequivocal for Indigenous knowledge resources to remain under their

ownership and control. Protocols include:

- National Inuit Strategy on Research (with special attention to NSIR Priority Area 4: Ensure Inuit access, ownership, and control over data and information)

- Circumpolar Inuit Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement

- CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance

- FAIR (Finable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) Data Principles – with Indigenous data, this is only employed with primary adherence to CARE principles

- OCAP, First Nations Information Governance Strategy

The digital infrastructure components of the knowledge mobilization system were designed and

chosen

based on the foundational knowledge model. A knowledge model maps out the semantic space (words and

concepts) of conceptual domains (wildlife genomics science; wildlife conservation; biodiversity and

environment; culture and social significance). This model defines the relationships between the

concepts, charting out useful linkages between relevant actors (persons, organization, participants)

and making explicit the connections between environment, actionable science, and cultural practices

and protocols. A graph structured database was chosen, as this structure was capable of retaining

the complex interactions between the concepts, and. could more closely conceptualize linkages to

concepts in our partner’s Inuit worldview, given the inherent interconnected nature of their

knowledge system.

The knowledge domains were modeled in a Resource Description Framework (RDF) structure, organized

with both Web Ontology Language (OWL) semantics and a series of Linked Open Data (LOD) vocabularies

and taxonomies. The development of this knowledge model used a socio-technological approach. A

socio-technical system includes various kinds of technology (that is not confined to information

technology), technical processes, and social processes. Socio-technical refers to the

interrelatedness of social and technical aspects of an organization or systems as a whole. A

socio-technological approach helps to formulate the organizational requirements to embed social

processes (like cultural practices) into technical systems. The knowledge graph in our system is an

example of computer interpretable knowledge that is expressed or defined by the knowledge model. It

serves as both a database and searchable network of real-world entities and the relationships

between them. Co-development with partners who articulate the cultural practices and protocols is

paramount to achieve this.